Historic Photos Out West

Welcome on in! Here's some photos from the Montana Historical Society about life in Out West!

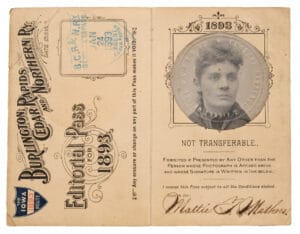

Raill Road Press Pass

Mattie Cramer, a newspaper editor from Iowa and New York, moved to Malta in 1908 with her young son and $100. She filed papers on a homestead claim for 160 acres, despite having little experience working the land. She became the managing editor of the Malta Enterprise, and her writing skills garnered a request from Great Northern Railway authorities to submit a testimonial letter regarding her homesteading perspective. Specifically, the railway wanted Mattie to convince other single women that it was possible for them to come west and homestead, just like she had done. Mattie wrote skillfully of the challenges and potential rewards, using humor and offering practical advice. Between 1913 and 1915, she received hundreds of letters from women – and men – seeking information on how to file a claim, what supplies to bring, and what to expect when homesteading in Montana. Mattie eventually moved to Great Falls, where she continued writing until her death in 1959. Her papers, including this press pass, provide invaluable insight into the lives of those who faced the challenges of homesteading, many of whom were not farmers by trade. Her collection complements the many other records of homesteaders found throughout the Montana Historical Society’s archives. Together, these diaries, writings, letters, and reminiscences provide a colorful glimpse of Montana’s homesteading heritage. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

Amskapi Piikuni Elk Tooth Dress

This elk tooth dress dates to before 1860 and originally was owned by Marguerite Black Weasel, a Blackfeet survivor of the 1870 Baker Massacre and the wife of trader Joe Kipp, according to a 1897 article in the Helena Daily Independent. Conservators estimate the 54-inch-long dress could date to as early as 1830. It consists of two expertly tanned hides, possibly from mountain sheep, sewn together with sinew. I originally was decorated with 192 elk “ivories” (eye teeth) but is missing a few of them. A single dress ornamented with 50 to 300 elk cuspids would have been worth at least two good horses. The first use of elk teeth as ornamentation was likely among the Mandans of the lower Missouri River region in the 14th century; from there, the practice seems to have spread to the Hidatsas, Cheyennes, Crows, Arapahos, Dakotas, Assiniboines, and Blackfeet by 1800. Today, both real and imitation elk eye teeth – usually carved from bone – are still used to decorate women’s dresses and often are worn as part of traditional tribal regalia by Montana’s Native peoples. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

Skull and Cross Bones

This wooden sculpture of a human skull and crossed femur bones was carved by Father Anthony Ravalli, a beloved priest who ministered to both Native Americans and non-Indians from the time of his 1845 arrival in the Bitterroot Valley until his death in 1884. An accomplished sculptor, Father Ravalli created this carving as a memento mori – an artistic convention dating from the Middle Ages that reminded viewers that death was inevitable, but adherence to Christian principles in this life ensured paradise in the next. He was born in Italy in 1812, and schooled in theology, medicine, mathematics, chemistry, philosophy, mechanics, architecture, and art. Father Ravalli arrived at St. Mary’s Mission in 1845, and devoted his life to serving the Salish Indians, the area’s original inhabitants. Father Ravalli became a fabled figure, assisting the sick, the wounded, and the dying. He also brought a set of French buhrstones from Europe, which were the first millstones of their kind in Montana. His compassion for natives and white settlers alike made him welcome wherever he traveled in Montana Territory. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

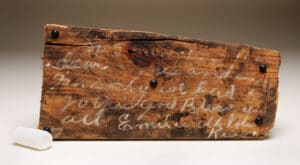

4) Chalk and Wood Message from the Smith Mine Disaster

At 8 a.m. Feb. 27, 1943, Emil Anderson and 76 other coal miners entered Smith Mine #3 near the community of Bearcreek. Less than two hours into their shift, a powerful blast sent soot and debris into the air. Only three workers escaped; 30 others died instantly. Forty-four later suffocated, and Emil Anderson was among this group. He had enough time to write a chalk message on the lid of a dynamite box: “It’s 5 minutes pass (sic) 11 o’clock Agnes and children I’m sorry we had to go this way God bless you all. Emil with lots (of) kisse(s).” This deeply personal and tragic farewell serves as a reminder of the worst coal mining disaster in Montana history, and is among the most poignant objects cared for by the Montana Historical Society. Coal mining began here in the 1860s with small enterprises providing fuel to local families and businesses. Major coal mines developed during the 1880s and 1890s, but a variety of factors caused most miners to shutter by the late 1950s. Today, the town of Bearcreek is mostly gone but the hard work and sacrifices of the coal miners who once made their homes there remain on the landscape and in the community’s memory. Artifacts related to the mines, like the delicate chalk writing on this wooden lid, provide a tangible link to this grueling and highly dangerous industry that was so central to Montana’s development. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

Symbol of the Pros

This larger-than-life bronze sculpture epitomizes the classic sport of bronc riding, an even tin which man and horse are pitted against each other in an eight-second whirlwind of muscle, fury, and bone-wrenching action. Artist Robert Scriver was born on Montana’s Blackfeet Reservation. Growing up among the vast plains and towering mountains, the young Scriver was influenced by the geography, people, and animals of the Glacier National Park area, as well as the romance of the Wild West. As an adult, he devoted his talents to music and taxidermy before becoming one of the nation’s most celebrated sculptors of Western life. Symbol of the Pros was completed in 1982 by Scriver and exhibited in front of his museum in Browning, one of a series devoted to the daring men and women of the rodeo. It stays true to the Pro Rodeo Cowboys Association, with a heavy wool-protected halter; a thick, square-woven hack rein attached to the halter; a regulation saddle with a high pommel; and the wool-covered flank strap, loosely attached to encourage the horse to kick higher. Following his death in 1999, his widow, Lorraine, inherited the daunting task of ensuring her late husband’s legacy be properly preserved. While art museums across North America coveted the world-class collection, Lorraine determined that these masterpieces rightfully belong where they could be treasured by the people of Montana. Today, the towering sculpture greets visitors to the Montana Historical Society, which also houses about 3,000 other Robert Scriver pieces. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

Holter Heart Monitor

To the untrained eye, this may look like a reel-to-reel recording system from the 1960s. But take a closer look and you’ll learn this is an “ambulatory electrocardiogram” aka the Holter hear monitor, named after Helena native and biophysicist Norman “Jeff” Holter. He came from a long line of tinkerers and entrepreneurs, with parents who owned a hardware store near Last Chance Gulch. After graduating from Carroll College in 1931, Jeff Holter earned degrees in physics and chemistry in California. After a stint in the Navy, he returned to Helena and established the Holter Research Foundation, initially located in the back of his parents’ hardware store. His foundation’s goal was to “follow whatever idea appears most likely to lead us to things not previously known.” With his partner William Glasscock, Jeff Holter developed a prototype for recording and observing the action of the heart. It was revolutionary because it was small enough to be carried alongside a patient, recording the person’s heart during regular activities. It entered commercial production in 1962. Today, smaller contemporary versions weigh less than cell phones and can be concealed easily under a patient’s clothing. But they’re still called Holter Heart Monitors, used in cardiology wards around the world. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

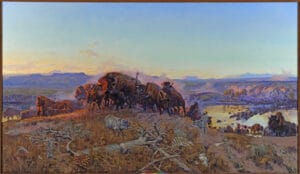

When the Land Belonged to God

Cowboy Artist Charlie Russell wasn’t much of a cowboy, but he truly captured the perceptions of Montana’s colorful past. Dramatic both in scale and visual impact, When the Land Belonged to God exemplifies Russell’s genius – an immense and masterful depiction of wildlife in what he called “the West that has passed.” Russell’s fondness for the West as it had been was unmistakable in most of his paintings of cowboys, Native Americans, and landscapes. He moved from the Midwest to Montana when he was 16 years old in 1880 to work on various ranches, where his sketch documenting the harsh winter of 1886-87 led to commissions for his work. He painted this 6-foot-by-3.5-foot work of art for Helena’s famed private gentleman’s Montana Club, which for decades played a key role in the social and political life of the Treasure State. It was installed in a prominent location in the club in 1914, and ultimately because the association’s most prized possession. Financial difficulties forced the club to sell the masterpiece, which was purchased by the state and is displayed at the Montana Historical Society to bring home to all Montanans the dreams of independence and reverence for nature, which underlie our quality of life, and what we work hard to nurture and defend. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

World War I Nurse’s Uniform

In June 1917, Virginia Flanagan of Great Falls was one of three Montana women selected during the first Red Cross call for nurses. Flanagan’s Army outdoor uniform was a wool skirt and overcoat with a silk blouse, along with sturdy leather boots and gloves. The leather soles on her boots are so worn the interior lining shows through – a testament to the long hours Flanagan spent on her feet, nursing the wounded. Her photograph album documents her service, including both joyful experiences and sorrowful moments. Flanagan mainly worked in medical units in France, but was able to travel around Europe as well. She has snapshots of soldiers and nurses, as well as the Great War’s devastation, including cities in ruins and trenches filled with corpses of German soldiers. She returned to Great Falls in 1919. Today, her uniform, photographs, and mementos embody the willingness of Montanans to pull together in turbulent times to protect their families, communities, and country. In the face of violence and fear, men and women such as Flanagan risked their own safety and comfort to care for strangers halfway around the world. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

Campbell Farming Company

In 1928, Time magazine dubbed Thomas Campbell the “Biggest U.S. Farmer.” But in later years, he also faced harsh criticism for his use of allotment lands taken from the Crow Reservation. Campbell was a native of North Dakota’s Red River Valley, and began working on the extensive family farm early in life due to his father’s poor health. He learned about innovative large-scale farming techniques in California, and in response to food shortages during World War I, he developed a controversial plan to mechanize food production and lease large tracts on the Crow and Fort Peck reservations. He started out as the Montana Farming Corporation with 95,000 acres, but later downsized to 50,000 acres – transformed to the Campbell Farming Company – after several years of drought led to paltry yields. He scaled up his effort to an unprecedented level, and a 1929 magazine article reported he could “plow 1,000 acres per day, seed 2,000 acres, harvest 2,000 acres, thresh 20,000 bushels of grain.” His industrialized dryland farming techniques were considered so cutting-edge that he was recruited as an adviser to the Soviet Union in the early 1930s. Campbell served in similar capacities in Great Britain, Tunisia, South Africa, and Australia. This photo is part of an extensive collection of documents, photographs, and films related to the Campbell Farms operations and housed at the Montana Historical Society. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

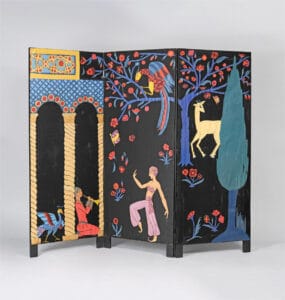

Dressing Screen

This screen initially was acquired by an antiques dealer from the estate of “Madam E.F.F.,” owner of the Richmond Apartments in Butte’s once-thriving, two-block red-light district. Allegedly used in a brothel as a dressing screen, the object is suggestive of the illicit past that Montana historian Ellen Baumler described as “the widest open town in the wide-open west.” By 1890, Butte counted six “luxury parlor houses,” numerous brothels, and hundreds of one-room closets, or “cribs, and the town was compared to much larger vice-ridden districts in San Francisco and New Orleans. The so-called “public women” caught the attention of potential customers by tapping on the ground-floor windows with thimbles, rings, knitting needles and chopsticks. Along with the women and their clientele, other individuals and institutions profited from the prostitution business. The Anaconda Copper Mining Company recognized it kept workers distracted and less likely to try to organize. The city coffers benefited by brothels’ rents, fines, and protection fees. Wealthy businessmen saw red-light real estate as a lucrative investment. Conversely, prostitutes faced considerable risk and poor working and living conditions. Between 1910 and 1916, about 1,000 women worked in the district, with many struggling to secure adequate food, housing and access to reproductive healthcare. The business both peaked and declined in 1916, when the rising threat of venereal disease prompted a federal crackdown. Shortly afterward, their operations literally went underground, with Butte places of ill repute relocating to basements, alleyways and tunnels filled with cribs. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

John Voorhies’ Pocket Watch

John H. Voorhies worked as a railroad conductor for the Northern Pacific Railway in Glendive at the turn of the 20th century. He used this watch, which bears the Northern Pacific’s red and black monad, to ensure that trains ran on time – a necessity for both safety and efficiency. Montana’s first trains covered distances in a fraction of the time previously possible on horseback. That necessitated more consistent methods of time management. For much of the 19th century, everyday people used local time – based on a clock in a centralized part of the municipality – and solar time, using the sun’s location. America’s railroad companies, however, used their own time measurements, as they required precision to coordinate the trains’ schedules as they traveled cross-country through more than 100 local time zones and 53 railroad time zones. On Oct. 11, 1883, delegates from railroad companies across the country met at the General Time Convention and established the Standard Time System. They divided the country into five time zones, each one hour ahead of the time zone to the west. This new system was adopted Nov. 18, 1883. That didn’t mean everyone accepted the new system. One Helena newspaper reported that many area residents were “letting loose on bogus railroad time and setting their clocks to true solar time.” Standard Time needed to rely on the accuracy of the clocks, so in 1887 the General Time Convention required all railroad watches be examined by a “responsible watchmaker every six months to ensure they did not run fast or slow by more than thirty seconds per week.” By 1893, almost all U.S. railroad companies accepted that requirement. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

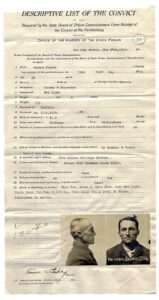

Herman Bausch’s Prisoner Description Sheet

During World War I, the persistent anxiety of war and notions of loyalty clashed, tearing apart communities across the United States. The prison record of Herman Bausch, who was jailed for sedition in 1918, captures this painful time in Montana’s history. Bausch originally was from Bavaria but was a naturalized American citizen who farmed west of Billings in 1915. He ran afoul of the local “Council of Defense,” which had the ability to prosecute those who apparently didn’t show enough support for the war. For Bausch, that mean his refusal to purchase war bonds. Some local men threatened to hang Bausch in front of his wife and young son if he didn’t purchase the bonds. Instead, they interrogated him for hours at the local Elks Lodge, where Bausch tried to explain that he didn’t care who won the war; that the United States shouldn’t have entered the war; and that they should stop sending ships with supplies and ammunition to our soldiers. His responses to the abuse by the local men became the basis for his sedition conviction. He served 28 months in the Montana State Prison. During that time, his child died from dysentery. Released in 1920, the affects of his incarceration lingered for years. In 2005, students and faculty at the University of Montana launched the Montana Sedition Project, where they researched all those convicted under the state’s Sedition Act of 1917. Thanks to their efforts, all 79 convictions were posthumously pardoned in 2006 by Gov. Brian Schweitzer. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

Child’s Polio Braces

Nearly every summer throughout the early 20th century, the poliomyelitis virus swept through the United States. Attacking the nervous system, the virus causes severe respiratory difficulty and muscle atrophy, and can lead to permanent paralysis and even death. In 1916 alone, 6,000 American children died and 27,000 more were crippled in the national polio epidemic. St. Vincent’s Hospital in Billings became an early center for treating children crippled by polio. Later, families across Montana brought their children to Shodair Children’s Hospital in Helena. Polio menaced children throughout the 1940s and 1950s. In 1954, children in four Montana counties took part in clinical trials for a “killed virus” polio vaccine, which was the largest of its kind in U.S. history. The vaccine worked. It was safe and effective. By 1960, polio cases fell to 100 per year nationally – a grand victory considering that in Montana alone it had more than 100 cases per year between 1950 and 1954. This set of child’s braces is heart wrenching to view. They measure just 22 inches from the shoe plate to the waist, which is about the size of a child 2 or 3 years old. The leather belt helped secure the rigid metal braces around the waist, while shorter straps known as “sleeves” attached the irons farther down each leg. Hinged below the knee, the braces allowed some flexibility of movement but not much. These braces were found stuffed in a crawl space during the 2015 renovations to the building that housed Shodair Hospital from 1938 to 1997. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

Assiniboine or Sioux Painted Buffalo Robe

Fort Peck trader Howard M. Cosier acquired this rare and magnificent robe in the 1880s. Robes showing images of personal exploits generally were created by men, whereas robes with geometric patterns – like the feathered circular patterns or multitiered war-bonnet motifs seen here – were painted by women. This robe contains four concentric feather patterns decorated in blue, red, and brown pigment with white accents. It’s corners are embellished with light orange details, and each feather is adorned with a red line that flares at the tip. Likely made between 1840 and 1850, robes of this kind were worn by men of several tribes of the upper Missouri – the Mandan, Hidatsa, Sioux, and Assiniboine. Hides like this were harvested in the winter when the buffalo’s hair was the thickest. The hide was scraped of all flesh, tanned using the brains of the buffalo, then stretched and rubbed until soft and supple. The finished product was pliable yet extremely strong. The edges of this robe display the holes made with it was stretched and staked to the ground. The ears and the tail of the animal remain, and the rest of the head has been carefully stitched flat. Today, its colors from berries, earthen pigments, and other materials remain vibrant and fresh, and it is as soft and warm as it was the day it was made. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov

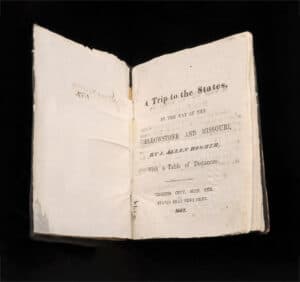

A Trip to the States

This slim, hand-sewn travelogue is not the oldest or most beautifully bound volume in the Montana Historical Society’s rare book collection, but it is one of the most valued. The book is based on the diary entries of John Allen Hosmer, son of the first chief justice of Montana’s territorial supreme court, Hezekiah Hosmer. It recounts his family’s journey from Virginia City to Detroit, Michigan, in 1865. It’s 1867 publishing is credited as Montana Territory’s second published book, and the first copies sold for $1 in gold dust. Due to the scarcity of even rudimentary printing presses in Montana at the time, publications prior to 1891 are extremely rare. This booklet is considered a gem, even though Hosmer’s book was printed on a tiny press, one page at a time. With a limited number of typeset pieces – he had scarcely any capital letters and put commas where there should have been period – Hosmer apologized to his readers in the foreword. The front and back covers, stitched by Hosmer himself, consist of cardboard sheets, pasted over with butcher paper, and wrapped in brown cloth. The value of the book today is incalculable, both as an example of early publishing in Montana and for its description of the trials of an overland journey through the region. It’s pages depict cross-country travel through the eyes of a teenager and document an exciting chapter in the story of an extraordinary American family. Learn more about this and other objects at the Montana Historical Society by visiting or purchasing a copy of the book “A History of Montana in 101 Objects,” available in the MHS store or online at mhs.mt.gov