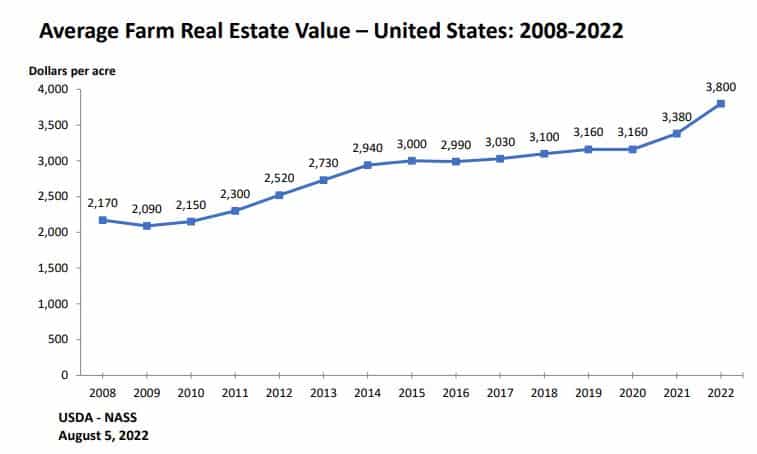

U.S. farmland prices increased 12.4 percent over the last year, according to new data from the Department of Agriculture.

USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service released the 2022 Land Values Summary that showed the largest numerical increase since the survey first began in 1997 and the largest percent increase (12%) since 2006. This annual report provides one of many indicators of the overall health of the agricultural economy and illustrates yet another heightened production cost and barrier to profitability faced by farmers and ranchers.

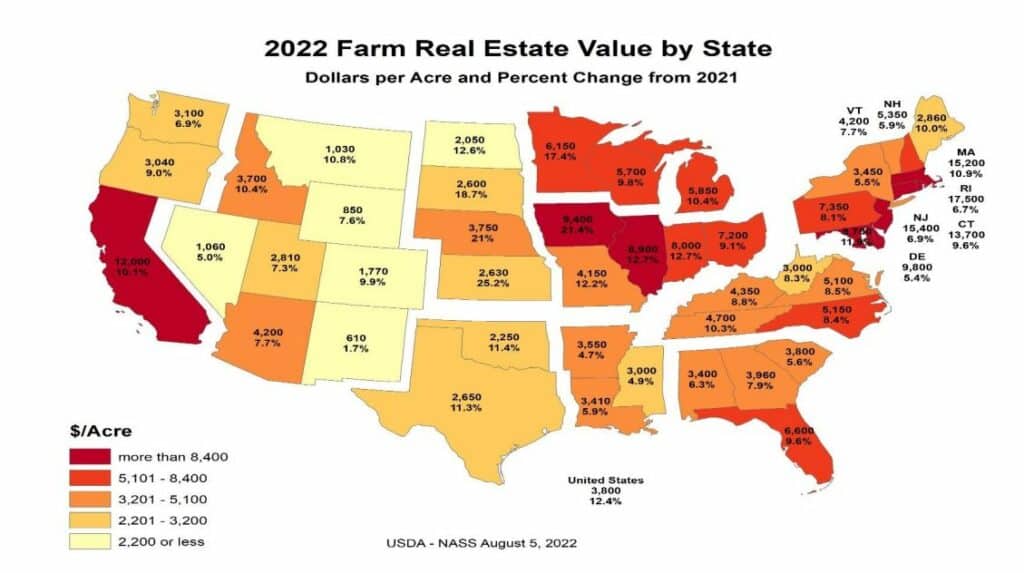

Farm Real Estate Value

U.S. farm real estate value, a measurement of the value of all land and buildings on farms, averaged $3,800 per acre for 2022, up $420 per acre from 2021. These levels vary significantly throughout the country, with the highest real estate values concentrated in areas of the country with larger volumes of high-value crops (think wine grapes and tree nuts in California), as well as areas experiencing upward pressure due to proximity to urban areas with little remaining developable land.

Part of this increase can be linked to the rise in commodity prices that have translated to a higher farming value for land in row crop-heavy heartland states like Iowa, Illinois and Indiana. Incentives added to government programs, such as those added in 2021 to the Conservation Reserve Program, that provide financial compensation to landowners who voluntarily enroll and retire highly erodible and environmentally sensitive lands also contributed to increased competition for active cropland, increasing land prices.

In Northern Ag Network’s region, the highest farm real estate value was in South Dakota at $2,600 per acre, up 18.7% from 2021. North Dakota farm real estate was 12.6% higher at $2,050 per acre. Montana up 10.8% at $1,030 per acre and Wyoming up 6.9% at $850 per acre.

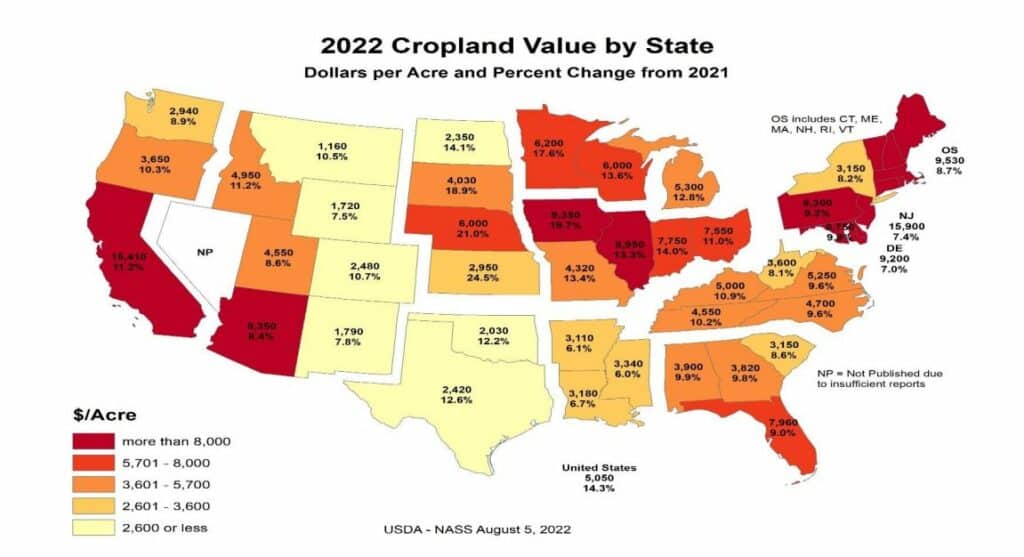

Cropland Value

The U.S. cropland value averaged $5,050 per acre, an increase of $630 per acre, or 14.3 percent, from the previous year. This increase came in as a 14% jump over 2021, which matched the increase in cropland in 2013 and is only outpaced by 2005 when rates jumped 18%. In dollar values, this year-over-year increase was $630 per acre, also a record numerical increase.

South Dakota cropland increased 18.9% to $4,030 per acre, North Dakota up 14.1% at $2,350 per acre. In Montana, the all cropland average came out at $1,160 per acre, up 10.5%. Irrigated ground increased even more up 14.8% to $3,500 per acre, non-irrigated up 9% at $910 per acre. In Wyoming, the all cropland average was up 7.5% at $1,720 per acre. Irrigated cropland up 7.8% at $2,750 per acre and non-irrigated up 5.6% at $940.

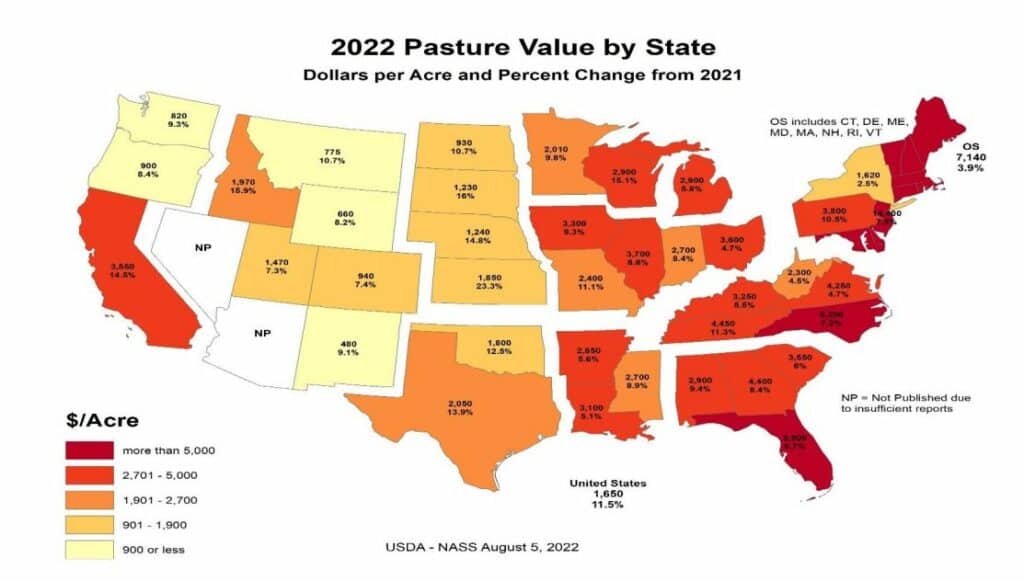

Pastureland Value

Finally, the U.S. pasture value averaged $1,650 per acre, an increase of $170 per acre, up 11.5 percent from 2021. This is an increase of 11.5% over 2021, the highest increase since 2006’s 30% increase and following seven years of little to no increases in value. With extended drought impacting 60% of the Western U.S., reducing the quantity of grazable land, demand for pastureland has increased. This has increased pastureland prices more broadly but has targeted areas with less density of high value row crops and more regular precipitation such as the South and Midsouth.

Again in Northern Ag Country, South Dakota saw the largest percentage increase with pasture values up 16% at $1,230 per acre. North Dakota up 10.7% at $930 per acre. Montana saw pasture values climb 10.7% to $775 per acre and Wyoming up 8.2% at $660 per acre.

Cash Rent Increases

On Friday, NASS also released data on cash rents, and so far the strong increases in land values have translated to moderate increases in cash rent. This tends to be more of a lagging indicator, and likely will be reflected in future negotiations that producers have with their landlords.

Average U.S. cropland rent increased to $148 per acre this year, an increase of 5% over 2021. Irrigated cropland rents increased 4.6% to $227 per acre, while non-irrigated cropland rents increased 5.5% to $135 per acre.

Cash rents for pastureland had the largest increase between 2020 and 2021, coming in at $14 per acre this year or 7.7% higher than last year. With drought across the West reducing the quality of public rangelands, demand for scarce leased private range has likely driven up these rental costs at a higher rate than other ag land as ranchers scramble for alternatives to graze livestock.

Margins for producers who rely on rented land are jeopardized by even marginal changes in rental rates. The higher rates rise, the fewer acres farmers can afford to rent, reducing their annual production output. More broadly, those who lack equity from land ownership have reduced access to operating lines of credit needed to fund annual equipment and input purchases; and the variation in their land cost can often take away the benefits of high crop prices.

In a period of heightened input costs across the board further exacerbated by inflationary pressures, high rent and land costs are yet another hurdle for farmers and ranchers working to produce more crops and raise more livestock. Fortunately for producers who own land, their equity has increased, but for those just starting out or reliant on the acres they rent to make ends meet, these increases can become an unbreachable barrier to entry.

###

USDA-NASS/NAFB/American Farm Bureau Federation – Market Intel